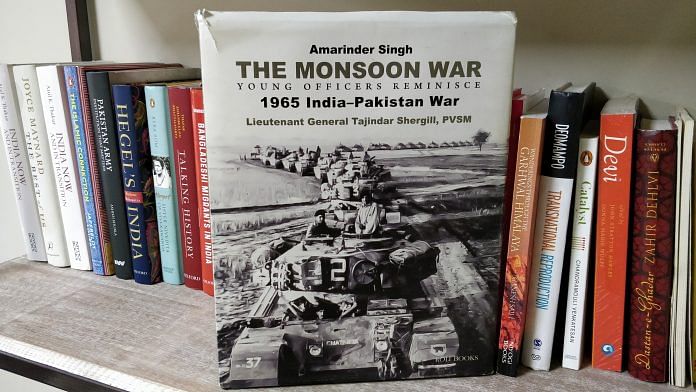

On the 52nd anniversary of the armoured operations, here’s an excerpt from Amarinder Singh and Tajinder Shergill’s book ‘The Monsoon War: Young Officers Reminisce’.

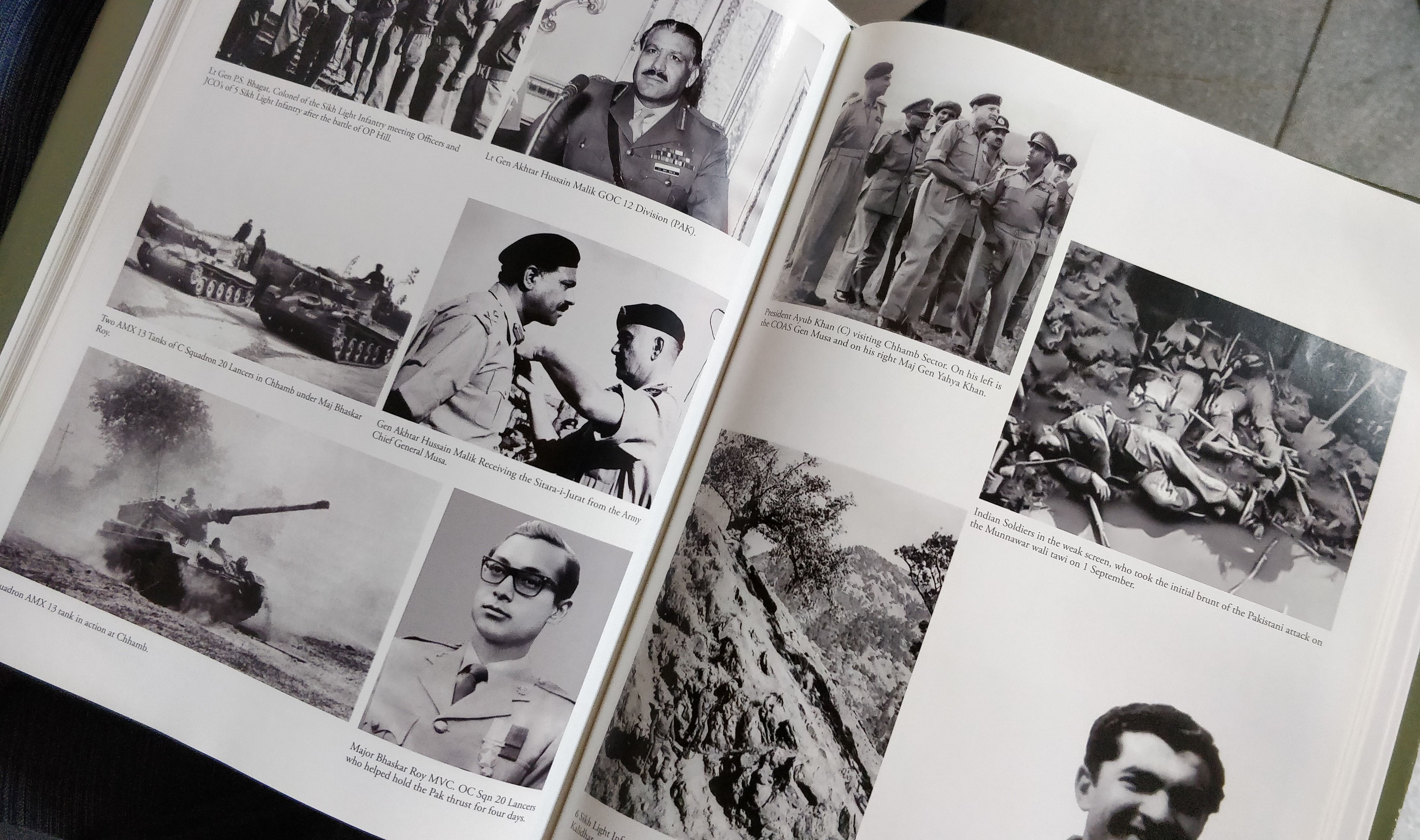

The armour operations by India from 7 September to 11 September were very well executed. Two squadrons of the division armour regiment 9 Horse integrated themselves into the main defences and along its flanks. This design of battle forced enemy armour to attack tanks and anti-tank weapons and at the same time was good for infantry morale that had suffered severely on 6 and 7 September. The Commander of 2 (I) Armoured Brigade had been proactive by establishing a liaison with 4 Mountain Division and acted, without informing the headquarters of XI Corps, to come to the assistance of 4 Mountain Division to save a critical situation and change the balance of armour forces in favour of the division. The design of the battle to trap the western offensive by enemy armour and destroy 4 Cavalry on 10 September will long be remembered as a classic armour defensive-offensive battle. That enemy operations in the Khemkaran sector ceased was not a consequence of this well-won battle, but a result of the scare of the events at Barki and more importantly, the battle won by 1 Armoured Division at Phillora on 11 September. This prompted the move of 3 Armoured Brigade out of the sector by the evening of 10 September, closely followed by the rest of 1 Armoured Division on the night of 11-12 September. The scare at Barki was a blessing in disguise for GHQ Pakistan, with the rampaging of the Black Elephant at Phillora, 3 Armoured Brigade — all ready for a move to Lahore — could swiftly be deployed in the Sialkot Sector; the General Headquarters of Pakistan therefore, wisely shifted their strategic weight into the threatened Rachna Doab. India, however, stood rooted in its inflexible strategic design.

The operations of 2 (I) Armoured Brigade after 11 September, controlled by headquarters of XI Corps, were those of a fire brigade that heard of imaginary fires here, there and everywhere that could have been dealt with much less armour. It was no longer independent or an armoured brigade. One more armour headquarter was raised, the Bharat Force with two armoured regiments but neither this nor 2 (I) Armoured Brigade were employed in a concentrated manner. There was ample scope to send 2 (I) Armoured Brigade to the Sialkot Sector to supplement 1 Armoured Division or on an independent thrust line in the Rachna Doab. A possible strategic victory in Pakistani Punjab was snatched from India by an act of self-preservation in XI Corps zone. The major defeat of Pakistan armour in the Khemkaran sector was because of 2 (I) Armoured Brigade and 9 Horse and in their success, the dogged infantryman played a large share through his intrepid employment of anti-tank weapons. 4 Grenadiers and 18 Raj Rif were the islands of resistance upon which the Pakistani offensive was shattered. It augured well for infantry tank integration in the future.

4 Mountain Division, the Pakistani 11 Infantry Division and 1 Armoured Division, all carried out operations without knowing enough about the enemy. They continued to rely upon whatever was fed to them by higher headquarters and made few efforts to acquire information. 4 Mountain Division had no AOP or helicopters for Commanders, Pakistan divisions had both. 4 Mountain Division relied upon information from headquarters XI Corps and headquarters of the Western Command and paid for it with casualties and destruction of equipment on 6 September, 12 September and 22 September. On 10 September, 1 Armoured Division and 4 Armoured Brigade were defeated by terrain that — with all their reconnaissance capabilities — they could easily have overcome; 4 Cavalry had ceased to exist even before 3 Cavalry delivered the coup de grace.

As regards casualties to tanks and armoured personnel carriers (APCs) from 18 to 22 September, the tanks left with Pakistani armour in the Khemkaran Pocket were, 4 Cavalry, one troop or four tanks; 6 Lancers, three troops or twelve tanks; 24 Cavalry, two troops and those with regimental headquarters 24 Cavalry, say twenty-one tanks; a total of 37 tanks out of 132 tanks of 4 Cavalry, 6 Lancers and 24 Cavalry. From 10 September till 22 September, nothing more had been made up by replacement or repair although crews were available to hold defended localities. For whatever reasons occasioned by warfare, ninety-five tanks were not available to go to war. According to Colonel Bhupindar Singh who had been to Patton Nagar after the 1965 war (Role of Tanks in the 1965 War):

According to Indian estimates, the Indians lost 32 tanks — two PT-76, three AMX, 12 Centurions and 15 Shermans. Indian Comdrs claim that Pakistan lost 97 tanks, a large number of them [about 72] were Pattons. 28 Pattons were captured intact; the remaining were either destroyed or disabled. All the Pak tanks were numbered under the arrangements of HQ XI Corps and there can be no doubt about the Indian claim.

In the matter of leadership, it is only Pakistan that can comment on their battle leaders as they have fuller information. What can be done is to see from the perspective of the Indian side which leader appeared to shine or otherwise. General Headquarters Pakistan can be found wanting for the faulty selection of inducting 1 Armoured Division into the Khemkaran sector after the monsoon and also for a nebulous command structure in the Khemkaran sector, where without a Corps headquarters, Major General Abdul Hamid Khan was made responsible for 1 Armoured Division and Major General Naseer Ahmad Khan, GOC 1 Armoured Division, felt he would come into the picture when the Patti-Harike line was handed to him. Both Major Generals seemed more like absentee landlords while the armoured Brigade Commanders continued with operations; there does not seem to be any instance when either of the two GOCs influenced the battle after the bridgehead. Brigadier Tony Lumb flogged his horse in the quagmire till it expired when he could well have asked his GOC to change his brigade’s thrust line. In all fairness to the Brigadier, he did ask GOC 1 Armoured Division to call of the offensive on 10 September when 4 Cavalry was near Lakhna; however, he was ordered to continue. Brigadier Bashir displayed laziness and indecisiveness which threw chances of victory away when 6 Lancers had outflanked the defences and reached the Valtoha railway station on 8 September and again on 9 September. Lieutenant Colonel Sahibdad Gul showed courage and innovativeness and was obviously a leader of men.

Lieutenant General Harbakhsh Singh and Lieutenant General J.S. Dhillon cannot be absolved from blame for the failure of 4 Mountain Division on 6 September for a too optimistic expectation of a ‘cold start’ and neglecting to deploy requisite resources in a sector they had analysed was the launch pad for the main Pakistani offensive. Lieutenant General J.S. Dhillon who washed his hands off the entire 4 Mountain Division when they needed him the most, showed that he was better suited to staff and not command in battle. Lieutenant General Harbakhsh Singh went wrong in his assessment of the withdrawal of 1 Armoured Division from Khemkaran and in his exuberance for pursuit and a whim, paid for it with his own battalion and the blood of others. Major General Gurbaksh Singh and Brigadier D.S. Sidhu showed their courage and resilience and rose from the ashes of defeat to success. Brigadier T.K. Theograj was the typical cavalry leader, wide awake, taking decisions on his own and with a flair for designing and fighting a mobile battle. Lieutenant Colonel A.S. Vaidya held his regiment together in the most adverse circumstances with antiquated tanks against tanks that were frontline tanks in NATO. Lieutenant Colonel Raghubir Singh of 18 Rajputana Rifles showed the spirit of the infantry at its best when the situation was at its worst; he held his battalion together and stood firm under difficult circumstances. Lieutenant General Harbakhsh Singh was strategically inflexible in shifting mobile forces to the Sialkot Sector and had he done away with his personal animosities, he would have won a strategic victory in Rachna Doab. Towards the end of the war he had planned to launch 23 Mountain Division with one squadron of 7 Light Cavalry, with PT-76 tanks, across the Ravi river to seize the Jassar area; he should have realised he could have given an independent thrust to the division with 2 (I) Armoured Brigade into Rachna Doab towards Sialkot. Perhaps the greatest example of higher personal leadership was displayed by Lieutenant General Harbakhsh Singh when Lieutenant General J.S. Dhillon had thrown in the leadership towel — he went to a defeated division, lifted a defeated leadership and set them on the path to a brilliant victory. At that moment he was worth one mountain division!

Even though 4 Mountain Division lost Khemkaran, Asal Uttar and Patton Nagar will live in the minds of India forever, sweetening a bitter early defeat and that is not a bad way to be remembered.

This excerpt is from the book ‘The Monsoon War: Young Officers Reminisce – 1965 India–Pakistan War’ by Amarinder Singh and Lieutenant General Tajindar Shergill which was published by Roli Books in 2015.